Raising Orphaned and Injured Possums

When you make the decision to get into wildlife caring, you really don't know what you're getting yourself into.

There are not many books on the subject, and the wisdom of the tribe is passed down by eccentric older women who have become embittered by a lifetime of caring for a magnificent species that is largely denigrated by the wider unappreciative public. The average punter does not understand that even the most common of possums is a protected species!

There is really nothing else to do but throw yourself into it without preconceptions, and hope you know what to do when you need to do it. Almost three years and 30 possums later, we can safely say that we know something about how to successfully take 40 grams of skin, bone and (if you’re lucky) fur, and raise it into a possum weighing from half to two kilograms and able to jump on your best curtains in a single bound.

Possums tend to come into care through a distribution network of wildlife carers. Just when the carer thinks "that's it, I'm going to have a rest for a while" they will be unable to resist a tiny little ringtail who has arrived into care after being found in a cat's mouth, or on the ground after falling off it's mother's back. The wildlife carer sees a defenceless creature requiring a mother (and bottle-feeds every four hours) and knows that this particular little creature's best chance of survival is with them.

Of course, many wildlife carers, through years of exposure to the cruelty of nature, are able to rationalize this mothering instinct into a rational calculation of natural selection, but when you first start out (and sometimes even three years later) you are overwhelmed by the beauty of these creatures.

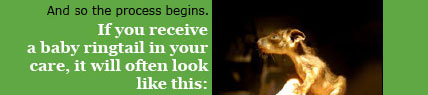

This little one is probably less than 50 grams and still has the "sleek" fur characteristic of the baby ringtail. It sleeps a lot and if it had its real mother, would be in her pouch suckling on her nipple.

Her mother is not around however, so this baby needs bottle feeds every few hours. Of course, there are many things to learn with bottle feeding, such as temperatures and hygiene etc. Also, the baby should be in a warm pouch, so she needs to be kept warm constantly. When you finally get sick of reheating water bottles, you go out and buy a heating pad and wonder why that particular decision took so long. Once the baby ringtail gets past its "sleek" phase, its fur goes all shaggy and you know that it is past the "danger" period.

Thankfully we have only lost a couple of babies along the way, and they usually had problems when they first came into care such as septicemia from cat bites. Note to cat owners: KEEP YOUR CATS IN AT NIGHT!

It is always a good idea to pair your baby ringtails up together, as they are a sociable animal and if you can get four together, even better:

As they grow up, they need more and more space, so be prepared to have a very large aviary for them to experiment in. They love to jump!

If you are just starting out in wildlife caring, you may be tempted to set up your bedroom as a temporary forest. Not the best idea unless you enjoy finding sticks and leaves in your underwear:

The ringtail possum in its natural habitat will climb through brush and shrubs, as well as trees, and transfers its weight through fairly light branches. It needs to practice this skill.

The entire aim of raising possums, however, is to release them! In fact, you are only granted a permit as a wildlife carer if this is your aim.

You cannot keep any Australian wildlife as a pet!

And they certainly are not pets. As much as you might get attached to a possum, you know that in their little hearts they are thinking of a life in the trees. And so, when the little ringtail gets to around 300 to 500 grams in weight, the carer's thoughts begin turning to the release of the animal.

By now, the possum is existing entirely on a diet of natural leaves and flowers, which the dedicated carer has to go out collecting each night and hanging in the (lucky) possum's cage before it wakes. It has been weaned off milk, and is jumping from branch to branch in its aviary as if to say "look Mum and Dad, it's time I got out amongst real trees." There is nothing like the first time your juvenile possum jumps...

By the time the juvenile-adult possum is ready to be released, it is between 500-700 grams in weight and looks like this:

Of course wild possums ready for release shouldn’t let their Mum’s hug them, but forgive us, this particular possum was our first ever, and we never did it again (except on special occasions).

There are two schools of releasing possums: the "soft-releasers" and "hard-releasers". As you could probably guess, we are "soft-releasers".

We have been very lucky to have a friend who lives around the Healesville region, who has taken all of our possums over the years and soft-released them for us on her property.

Soft-releasing means that the animal is allowed to acclimatize the local areas food and smells, away from human contact, and after a period of time has passed (2-6 weeks usually) the door to their outside aviary is left open and they leave when they want to.

Some possums have been known to keep coming home for up to a week, but eventually they don’t return hopefully they have discovered their freedom.

Hard-releasing means going into a location and hanging your possum’s box (or drey) in a tree and allowing it survive from there. To us, this seems like a fairly random process that must be shocking to a possum, and unlikely to have the best results in terms of its long-term survival.

Some of the "hardcore" carers advocate that possums should only be taken into care if you know where the possum was found, so that when it is ready to be released, it can be returned to where it came.

We are not sure if this is based on scientific fact, or whether there are so many animals needing care that this is a way of saying no to a percentage of animals thereby reducing the load of the over-taxed animal carer. One thing we do know is that if you were to apply this rule diligently, then thousands of possums would be euthanized each year in Victoria alone.

We are not sure if we are making a difference to the plight of the possum, but we know we have saved the lives of some thirty or so possums in our time, and each one of these gave us joy as if they were our own children.

It has given us a perspective on life that decrees all life to be precious, although to be honest, we probably had that before we began this work. We are inspired by the older, seasoned carers who (although bitter and twisted) devote their lives selflessly to animal welfare. These people are truly enlightened.

So that's the end of this particular story. It has mainly focused on the ringtail possum. Wait until next time when I tell you about the brushtail possum and our experiences with that crazy character!

by

A Passionate Wildlife Carer

Love and Light

Vine